This story was produced by FairWarning (www.fairwarning.org), a nonprofit news organization based in Southern California that focuses on public health, consumer, labor and environmental issues. You can sign up for their newsletter here.

In May, a 9-year old girl, was taken to an emergency room after swallowing three powerful magnets made by a company called Zen Magnets. According to a government report, which did not name the child, the magnets punched holes through her intestines.

Such tiny rare earth magnets were to have been banned several years ago to prevent just this kind of life-threatening injury. But the move was blocked by litigation between Zen and the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, which won an important round just weeks ago.

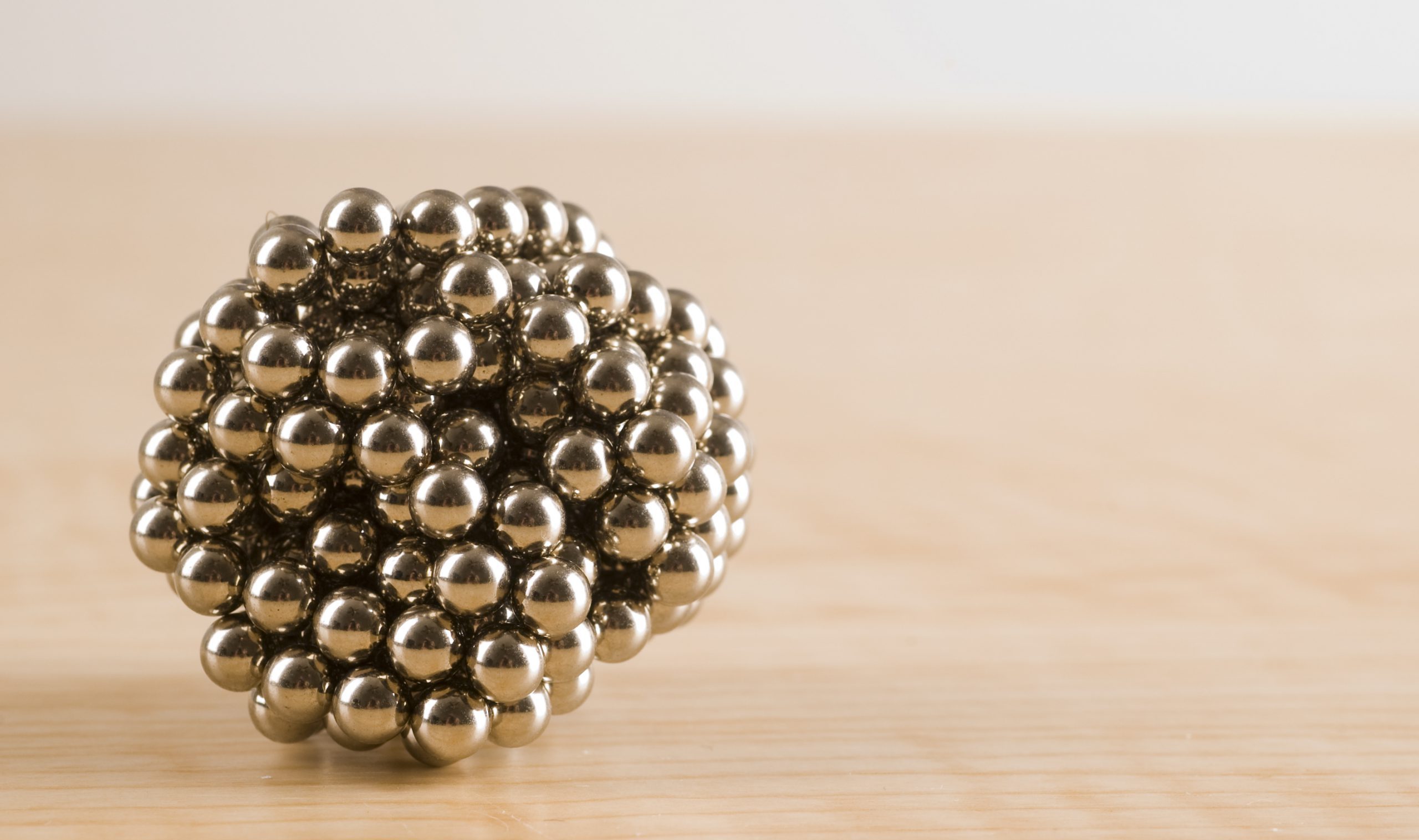

Rare earths are used in electronic devices, magnets and other products. Tiny magnets made of these minerals first appeared on the market in 2009. Often as small as BBs but significantly more powerful than refrigerator magnets, they’re sold in sets of hundreds and marketed to adults as novelty desk toys. But many parents buy them for children, too, not realizing that toddlers may swallow the tiny spheres, which resemble colorful candy. Even older kids can accidentally swallow them, sometimes by using magnets to mimic tongue or lip piercings. When two or more magnets enter the body, they can pinch together and inflict horrific injuries.

Over the past decade, thousands of children have been treated at emergency rooms after swallowing high-powered magnets, according to CPSC estimates. Parents and doctors reported cases of children who were hospitalized with injuries such as perforated intestines and bowels. At least two children in the U.S. have died.

In 2012, the agency filed an administrative complaint against Zen to force it to stop selling magnets, and followed up with a safety standard requiring magnets sold in sets to be less powerful and therefore less dangerous if swallowed.

But Zen, based in Denver, fought the recall and magnet rule, sparking a marathon legal battle across administrative and federal courts that has allowed the magnets to stay on the market and cause more injuries.

In 2016, the CPSC suffered a major setback when a federal appellate court vacated the magnet rule. That same year, an administrative law judge ruled that the agency hadn’t proven that warning labels alone would be inadequate to protect consumers. And in 2018, a federal judge ruled that Zen’s due process rights had been violated because one of the agency’s rule-making commissioners, Robert Adler, had made comments during a hearing that the court said had shown bias.

Finally in August, a three judge panel of the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the decision, stating in a unanimous ruling that there had been no violation of Zen’s rights and that the magnets could be recalled. But even now, the case may not be over; Zen has appealed for a hearing before the full court. Adler and a commission spokesman declined comment on the litigation, citing the Zen appeal.

The CPSC operating plan for 2021 mentions possible re-consideration of a mandatory magnet rule.

“It’s unfortunate because while the issues have lingered [in court], more children have been injured,” said Remington Gregg, an attorney with the advocacy group Public Citizen.

Many injuries could have been avoided with a safety standard, according to Bryan Rudolph, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore in New York City. In a study published last month, he and two co-authors found that magnet ingestions significantly increased in the years after the 2016 ruling that vacated the standard.

“Injuries are definitely going up,” Rudolph said. “Anecdotally, there is hardly a week that goes by now that I don’t hear from a colleague about another child who has been injured by these products.”

In December 2019, Rosalynd Darling and Gray Winslow rushed their seven-year-old daughter Amy to a New York City hospital after she accidentally swallowed several high-powered magnets while trying to pry them apart with her teeth. According to Darling, Amy got the magnets through a toy-swap with a friend at school.

“I wouldn’t have allowed her to have them if she’d been four, because you can’t have a toy like this,” Darling said. “But at seven, I wasn’t really concerned.” Amy recovered after doctors removed the magnets from her stomach through an endoscopy procedure.

Children can also get hurt by magnets pinching their ears, noses and genitalia, said Dr. Carl Kaplan, chief of pediatric emergency medicine at Stony Brook Children’s Hospital on Long Island.

“I had to remove one where the person swished them around in their mouth and they ended up on each side of the lingual frenum—the fleshy piece of tissue underneath our tongue,” Kaplan said. “That wasn’t easy because you have to pull the whole tongue out to get it out, which requires sedation.”

For their part, magnet companies, hoping to head off a mandatory standard, are developing a voluntary standard requiring warning labels but no change in the strength or size of magnets. Zen’s owner, Shihan Qu, who has also been involved with another magnet company, said in an email to FairWarning that stronger warning labels will help prevent injuries, especially if accompanied by child-resistant packaging, similar to what is used for medical marijuana or pharmaceutical drugs.

But even clear disclaimers and age recommendations have done little to stop consumers from purchasing magnet sets for children.

Reviewers on a Qu website, Neoballs.com, routinely report buying magnets for children. One reviewer said her six-year-old niece used magnets to make bracelets for friends. Another who purchased Neoballs for a seven-year-old said they liked buying from Zen because “I feel like I’m ‘sticking it to the man,’” apparently referring to the company’s years-long legal battle with the CPSC.

After FairWarning contacted Qu last month, his company posted responses to several reviews that mentioned buying magnets for children, cautioning that they are intended for people 14 and over. The review about the seven-year-old was deleted; in the one about the six-year-old, the child’s age was removed.

FairWarning also found reviewers on Amazon who reported buying magnets for children made by Speks, a company co-founded by Qu that he left in 2018.

“My five-year-old loves this toy,” one Amazon reviewer wrote about a Speks magnet set. The Amazon listing included a warning that the magnets aren’t meant for children under 14.

Speks has warned some customers who mention children in their reviews, but appears to ignore others. In October 2018, the company even thanked a reviewer who wrote that her 12-year old daughter loved Speks magnets.

Since 2018, consumers and physicians have filed three reports to a CPSC website about children who were hospitalized after ingesting Speks magnets. On Amazon, FairWarning found reviews about children swallowing Speks magnets. In its response to a recent review about a six-year-old who was hospitalized after he ingested several magnets, Speks said that its products are marketed and sold exclusively to adults.

Craig Zucker, the owner of Speks, told FairWarning that none of these incidents resulted in perforation injuries. Speks’ website advertises that the strength of its magnets is about 90 percent less than the ones the CPSC had sought to ban. In 2014, Zucker agreed to recall a different magnet product, Buckyballs, following reports of injuries.

Some public health experts like Bryan Rudolph doubt that small rare earth magnets can ever be safely sold to consumers.

“There are no good data to suggest what is a ‘safe’ magnet,” Rudolph said. He noted that the CPSC’s vacated standard mandated that magnets be relatively weak but that even weak magnets can become lodged in a child’s appendix or intestine because of their small size.

For example, in 2019 a five-year-old had to have his appendix removed after swallowing two magnets made by Speks, according to a report on a CPSC website that did not state where this happened.

“The bar should be very high to remove a product,” Rudolph said, “but I think we’re well beyond the bar at this point.”