During a trip to Colorado last summer, then-Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke stopped by the office of a small Denver-based oil and gas advocacy group called the Western Energy Alliance. It was the waning months of his embattled leadership at Interior before he would be ousted in December, but the group had been a strong ally, so he made time in his schedule to talk with its board.

In an email sent to members about the gathering, Alliance president Kathleen Sgamma gushed about Zinke’s support for her group and complimented his “energy dominance” plan — President Trump’s strategy for opening up federal lands to more petroleum production.

“We asked him how we can continue to support him and his staff, and he expressed appreciation for us taking a few of the bullets that come his way on controversial policy issues,” Sgamma wrote to Alliance members. “We have been at the forefront of explaining these policies in the media directly,” she added, “which helps him counter the disinformation that comes from the environmental lobby.”

But critics charge that Western Energy Alliance does more than take a few bullets and beat back critics of Trump’s environmental strategy. Behind the scenes, it is driving the agenda of the Interior Department, rewriting policies that hollow out protections for endangered species, while helping oil and gas companies gain easier access to federal lands and unravel rules that take a cautious approach to drilling.

“Fossil fuel interests are pulling the strings at Trump’s Interior Department, just as they did at Bush’s Interior Department,” says Congressman Raul Grijalva, D-Ariz., the new chairman of the House Natural Resources Committee. “Democrats on the Natural Resources Committee want to know how deep this influence runs and how we can break this cycle of making up rules to suit fossil fuel companies’ demands regardless of congressional intent or public opinion.”

Sgamma did not respond to multiple requests for comment and declined to answer questions regarding this story.

For many years, a main target of the Alliance has been the conservation plan for the sage grouse. Few Americans have seen or even heard of this chicken-like bird, but at one point around 16 million of them ranged across 290 million acres, an ocean of sagebrush across the West. Because of habitat loss caused by road construction, development, and oil and gas leasing, only 200,000 to 500,000 sage grouse remain today.

In 2010, a court ordered the federal government to either address this habitat loss or list the sage grouse under the Endangered Species Act. With only around half of the remaining sage grouse habitat on federal land, federal agencies began working with several governors and 1,100 ranchers across 11 states to protect and improve over 70 million acres of sagebrush. Finalized in 2015, the plan also provides habitat for over 350 different species, such as mule deer, elk, pronghorn and golden eagles.

“The effects of this plan touch so many species and stretches across several western states,” says Nada Culver, senior counsel with the Wilderness Society. If you wanted to undermine protections for endangered species, she says, it would be the place to start.

The summer after Trump entered office, Alliance president Sgamma wrote to the Interior Department to complain about the sage grouse. In her letter, Sgamma claimed that sage grouse management would cost more than 9,000 oil and gas jobs and impede $2.4 billion in economic growth. After examining correspondence between the Interior Department and industry lobbyists, the Western Values Project found that Trump officials accepted 13 of Sgamma’s 15 recommendations to alter sage grouse protection. When the administration released a revised sage grouse plan a year ago, Zinke sent an internal memo that reversed the Obama administration’s focus on developing oil and gas outside of grouse habitat.

“The laws provide the framework for federal policy, but federal agencies and officials have great latitude to interpret their legal mandates, to fill in the details of how policies should be implemented, and to assign priorities and budget resources,” says Bob Dreher, a vice president at the Defenders of Wildlife who previously served as legal adviser to several federal agencies.

In the last two years, Trump officials have offered approximately 1.5 million acres for sale in sage grouse habitat, with approximately 726,000 acres sold, says Culver. An additional 1 million acres in sage grouse habitat have been offered for lease in the early months of this year.

While the sage grouse has been a primary target, Culver says the Alliance has been most effective in opening up other areas of federal land for leasing and ensuring that petroleum production is deregulated. “It’s a two-step process,” she says. “The first is that you have to open the land for leasing, and they’ve focused on making sure that happens. Once you have the lease, you then have to consider where and if to drill. They have also made that easier.”

Last year, HuffPost reported that the Alliance made it easier for companies to avoid environmental concerns when drilling and The New York Times found that the Alliance had a hand in streamlining the leasing process so that citizens had less time to protest oil and gas leases. More than 12.8 million acres of federal land were offered up for leasing last year, triple the average under President Barack Obama’s administration.

“First and foremost, the oil and gas industry wants policy changes that let them put more holes in the ground as soon as possible before this administration ends,” says Jesse Coleman, a senior investigator with Documented, a new a watchdog group that investigates how corporations manipulate public policy. Coleman notes that Trump political appointees make this happen with internal memoranda that respond to requests from the Alliance.

To buttress his claims, Coleman cites a 19-page letter Sgamma wrote to Zinke in August 2017 asking for a fleet of changes to how the department regulates petroleum production. The Alliance submitted the letter through the federal regulations.gov website, and its lobbyist then forwarded it to several agency officials.

“Kathleen and I would be more than happy to answer questions on these comments, and we look forward to working with you on any reform initiatives you undertake in the future,” wrote the Alliance’s lobbyist. “Thank you all for your hard work in DC!”

Zinke’s deputy chief of staff emailed back, “Thanks for flagging.”

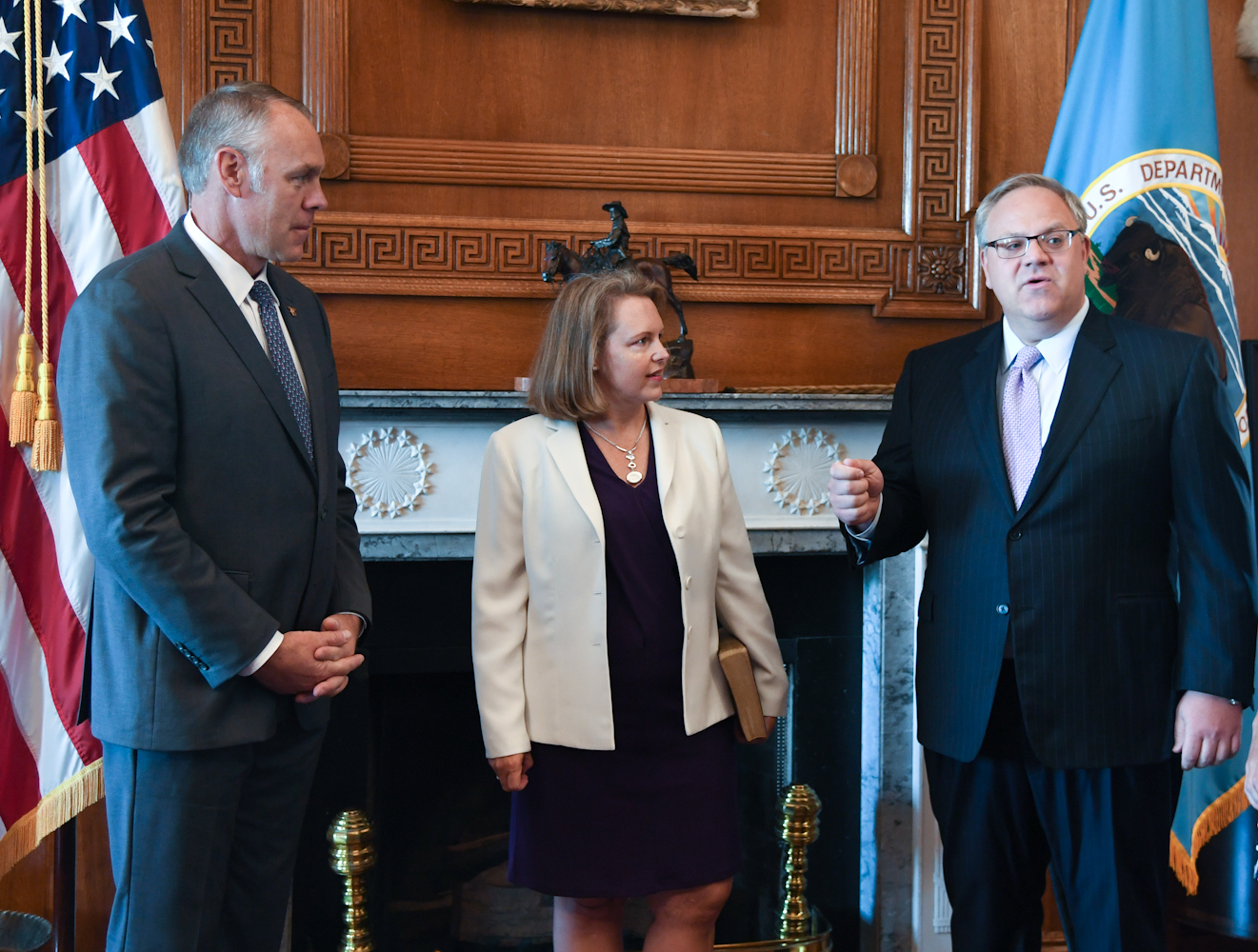

After reading the letter, Coleman began tracking department memos and digging through public records to find evidence that the Interior Department granted Alliance’s wishes. In late December 2017, Zinke’s deputy, David Bernhardt, sent a memo that responded to the Alliance’s wish to rollback “mitigation” measures instituted by Obama that incorporated climate pollution concerns into drilling plans. Coleman says that memo effectively ended any attempt by agency employees to force companies to mitigate the effects of oil and gas drilling.

Coleman found a second example in a department memo sent over the summer on drilling activity that affects a mix of federal and private lands. In the past, this triggered the need for an environmental analysis of the drilling impacts. But the June memo rescinded this requirement as the Alliance had requested.

Oil and gas development fragments and degrades habitat so that federal officials will no longer consider that land useful in species protection. “We’ve seen arguments from the oil and gas industry that once you have a hole in the ground, that land can’t be counted as habitat,” Culver says. She adds that leasing federal property drives a stake in the ground, marking territory as belonging to industry. “Once you have a lease, it’s there for at least 10 years. And it’s considered a right that is given a lot of deference by the federal agencies.”

“The Trump administration’s record at the Interior Department is clear: We are striking a balance between conservation and responsible energy development on federal lands,” says department spokesman Eli Nachmany. “Everyday Americans, like those who have spent time enjoying any of the hundreds of thousands of acres of public land on which this administration has opened or expanded hunting and fishing opportunities, understand this.”

Nachmany did not respond to questions about the Western Energy Alliance.

With Zinke gone from Interior, environmentalists say they do not expect the Alliance’s influence to abate since Trump nominated the deputy administrator, Bernhardt, as the replacement. Sgamma has praised Bernhardt as the man who has been running policy at Interior, and both he and the Alliance have similar allies.

(You can read more about the Interior Department’s acting administrators and whether the process used the last two years to place people in leadership positions may violate the Federal Vacancies Act.)

Prior to joining the administration, Bernhardt served on the board of a small nonprofit that works on endangered species policies called the Center for Environmental Science, Accuracy, & Reliability or CESAR. For many years, the Alliance has hired a scientist on the board of CESAR to conduct studies that it cites later in letters to the Interior Department as cause to roll back endangered species protection. While some media reports label CESAR an environmental advocacy group and others a think tank, the group is noted for taking stands on endangered species issues that favor industry.

CESAR has challenged the federal government’s science on endangered species such as the California delta smelt, and Bernhardt handled the recent rollback of smelt protections during his time as deputy administrator. CESAR’s website lists its executive director as Craig Manson, who was President George W. Bush’s key adviser on endangered species policy. A government report in 2008 named Manson as one of several political appointees who put pressure on Interior officials to reverse rulings on endangered species. Reached at the law firm where he now practices, Manson says that he has not been the executive director of CESAR for many years and that he has nothing to add about the organization.

CESAR’s home address in tax filings is the address for Julie MacDonald, a senior Bush appointee who was charged in an investigation by the Interior Department’s inspector general with interfering with scientific findings on endangered species. Reached at CESAR’s telephone number, MacDonald said she is not authorized to speak on behalf of the organization and is not aware of who funds it.

Critics say the Alliance’s close ties to CESAR will only make it more effective if the Senate approves Bernhardt’s nomination. “The Alliance, David Bernhardt and CESAR have worked together to pursue the same strategies to limit regulations on the oil and gas industry and harm endangered species for years,” says Coleman.

Rep. Grijalva is also disturbed. “As we’ve seen for years, this whole campaign is driven by a small group of closely connected extractive industry figures, including Deputy Secretary Bernhardt,” Grijalva said. “It has nothing to do with any legitimate public interest, but that hasn’t stopped Republicans in Congress or the Trump administration in the past and it won’t now.”

Paul D. Thacker is a journalist based in Washington, D.C., and Madrid. This story originally appeared on Yahoo News.