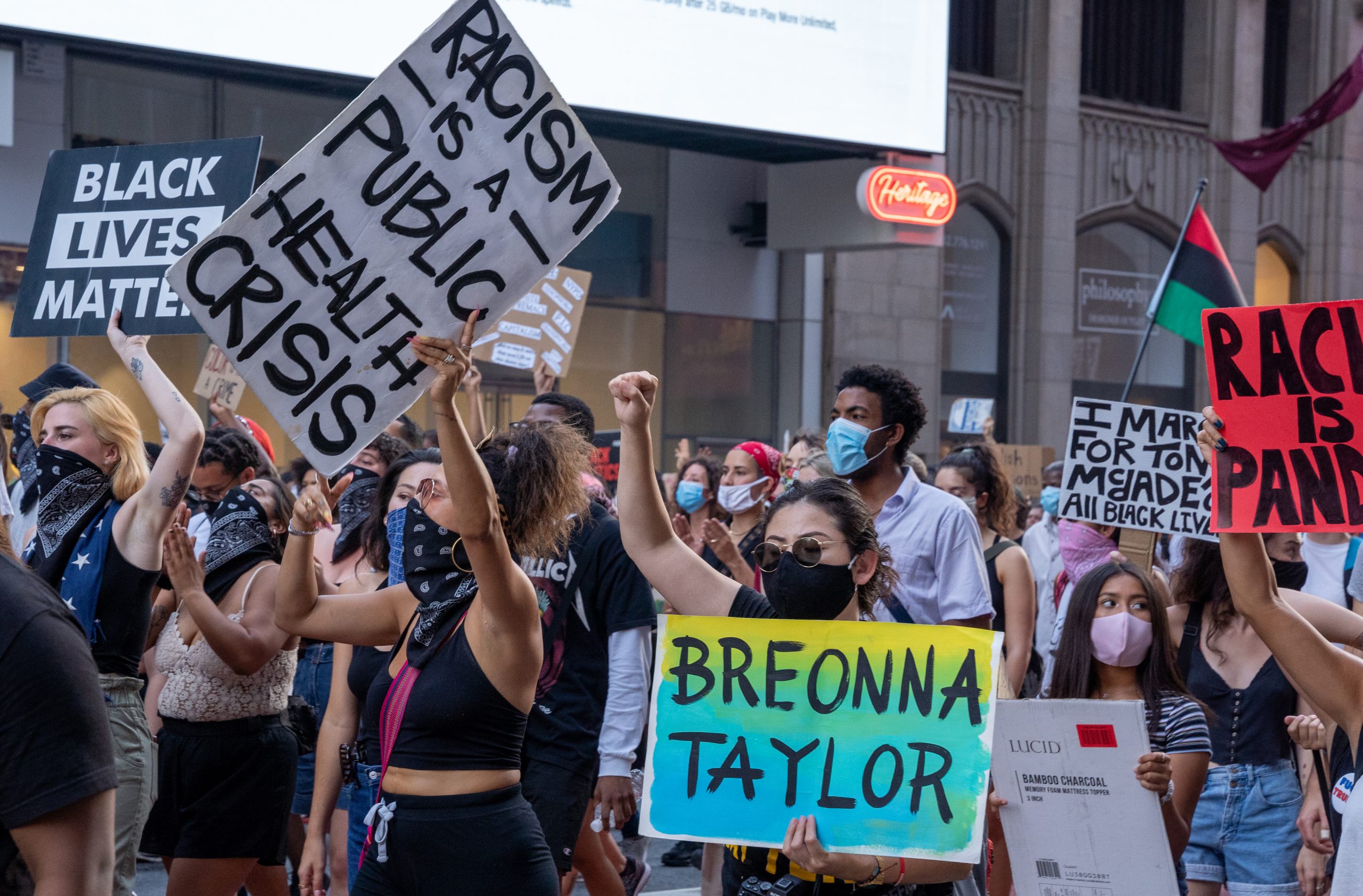

The fatal shooting of Breonna Taylor by Louisville police in March has made her name a rallying cry — #SayHerName — for policing overhauls and racial justice nationwide.

Her killing has also brought into focus an often overlooked but consistent subset of people fatally shot by police — women.

Since 2015, police have fatally shot nearly 250 women. Like Taylor, 89 of them were killed at homes or residences where they sometimes stayed.

After Louisville police fatally shot 26-year-old Breonna Taylor during a nighttime raid at her home in March, her killing could have been just another in a long line of deadly police shootings of women that have drawn little publicity.

But the death of Taylor, who was Black, fell between two high-profile killings of Black men. In February, a retired police detective, his son and a third man allegedly killed Ahmaud Arbery, 25, in a Georgia suburb. In May, a Minneapolis police officer knelt for nearly eight minutes on the neck of 46-year-old George Floyd, fatally injuring him.

Taylor’s name has become a rallying cry — #SayHerName — for policing overhauls and racial justice nationwide. Her image is on magazine covers, her name emblazoned on WNBA uniforms and more than five months later, protests over her death continue in Louisville. Her killing has brought into focus an often overlooked but consistent subset of people fatally shot by police — women.

Since The Washington Post began tracking fatal shootings by police in 2015, officers have fatally shot 247 women out of the more than 5,600 people killed overall.

The names of these women are often not as well known as the men, but their deaths in some cases raise the same questions about the use of deadly force by police and, in particular, its use on Black Americans.

The Post found only one other fatal shooting that closely matched Taylor’s case — a Black woman, unarmed, killed during a raid at home while a boyfriend shot at police. But 139 other cases shared one or more of the circumstances in which Taylor was killed.

Of the 247 women fatally shot, 48 were Black and seven of those were unarmed.

At least 89 of the women were at their homes or residences where they sometimes stayed. And 12 of those women killed at home were shot by officers who were there to conduct a search or make an arrest.

Since 2015, Black women have accounted for less than 1 percent of the overall fatal shootings in cases where race was known. But within this small subset, Black women, who are 13 percent of the female population, account for 20 percent of the women shot and killed and 28 percent of the unarmed deaths.

Black men, 12 percent of the male population, make up 27 percent of the men shot and 36 percent of the unarmed deaths.

Taylor’s killing came shortly after midnight on March 13, when plainclothes police officers used a battering ram to force their way into her apartment to execute a “no-knock” search warrant in a drug investigation. At the time, Taylor and her 27-year-old boyfriend, Kenneth Walker, were asleep.

Walker fired one shot with a gun he legally possessed, striking an officer in the leg. The officers returned fire, and Taylor, an emergency room technician, was struck five times.

Police said they identified themselves, but a lawsuit filed by Taylor’s family disputes that, and Walker said he thought the officers were intruders, according to local news reports. No drugs were found at the home. Charges against Walker for attempted murder of a law enforcement officer were dropped. The city has since banned the use of no-knock warrants.

The Louisville police chief fired one of the officers involved, Brett Hankison, for “wantonly and blindly” shooting 10 rounds into Taylor’s home in “extreme indifference to the value of human life,” according to the letter announcing his intent to terminate the officer.

In an appeal, Hankison’s attorney, David Leightty, wrote the officer should not have been fired, noting that the FBI and the Kentucky attorney general’s office were still investigating. “Brett Hankison did not ‘blindly’ discharge his firearm, and did not lack cognizance of the direction in which he fired, but acted in quick response to gunfire directed at himself and other officers,” Leightty wrote.

A spokesperson for the Louisville Metro Police Department and Walker’s attorney did not respond to requests for comment. Taylor’s family also declined to comment.

Taylor’s death “could have easily been forgotten, and it was almost forgotten,” said Kimberlé Crenshaw, executive director of the African American Policy Forum, a racial justice think tank which created the #SayHerName campaign in 2014 to elevate the stories of Black women killed by police. “But I think the fact that other cases were happening in the same season made it harder to simply overlook her case.”

Because women overall account for a much smaller number of people killed by police, Crenshaw said Black women often are left out of the public narrative about the use of force by police against Black people. Police have shot and killed 1,274 Black men since January 2015.

Crenshaw said Black women’s deaths also may be dismissed as “collateral damage” if they are killed while police are pursuing someone else. Twenty of the 247 women were killed in that kind of situation, analysis shows. In 12 of those 20 shootings, police said the women killed were caught in crossfire or shot accidentally.

“As long as Black women lose their lives in circumstances like these, their lost life won’t be dramatized in a way that mobilizes the kinds of reforms that have to happen in order to protect more life and to make police officers accountable,” Crenshaw said.

The shooting with circumstances most similar to Taylor’s killing is that of Alteria Woods, 21, who was killed on March 19, 2017, when members of the Indian River County Sheriff’s Office SWAT team went to her boyfriend’s family’s home in Gifford, Fla., to conduct a search warrant for narcotics, according to an affidavit filed by the sheriff’s office in court.

The deputies said they identified themselves and began breaking the bedroom window, and Woods’s boyfriend, Andrew Jeff Coffee IV, began shooting, the affidavit states. Deputies returned fire, striking and killing Woods, an unarmed Black woman.

Indian River County Sheriff Deryl Loar told reporters at the time that Coffee knelt next to Woods, who was in bed, and fired at deputies. One deputy was shot in the shoulder. “He used her for personal protection,” Loar said, according to TCPalm. The sheriff’s office did not provide a comment by publication time.

After he was arrested, Coffee said the deputies did not identify themselves and he did not know who they were. Coffee was charged with attempted murder of a law enforcement officer and other crimes related to drugs and a gun recovered at the home, court documents show. He has pleaded not guilty.

“As this case is on-going, we can only speak to the unnecessary tragedy of Ms. Woods’ death and the heartbreak of all those that loved her who still wait for answers and accountability,” said Coffee’s lawyers Adam Chrzan and Julia Graves in a statement.

Woods’s mother told The Post that Taylor’s death has been hard on her because of the similarities. “It brought back a lot of memories of our daughter’s murder,” Yolanda Woods said.

India Kager, 27, is also among the women killed when police said they were shooting at someone else.

On Sept. 5, 2015, Virginia Beach police officers in two unmarked cars were surveilling 35-year-old Angelo Perry, the father of Kager’s child. Police said Perry was a suspect in two homicides and a home invasion, and they believed he was on his way to kill a member of a rival drug gang.

The officers followed Perry, Kager and their 4-month-old son as they drove into a 7-Eleven parking lot. The police cars pulled up behind Kager’s Cadillac, blocking it in.

An officer threw a flash-bang grenade toward the Cadillac to distract Perry, Virginia Beach Commonwealth’s Attorney Colin Stolle later told reporters. Four officers ran toward the car to arrest Perry and he shot at them.

The officers fired 30 rounds in response, killing Perry and Kager. Police said the infant, sitting in the back seat, escaped injury. A nearby surveillance camera recorded the gun battle.

Stolle concluded that the police shooting was justified.

In 2018, a jury in a wrongful-death civil suit filed by Kager’s family determined that two of the officers acted with “gross negligence” and awarded the family $800,000. The city settled the case to give closure to Kager’s family and to the officers, said Julie Hill, a spokesperson for the city of Virginia Beach.

Gina Best, Kager’s mother, told The Post that her daughter and Perry were on their way back to Maryland from Virginia Beach, where they introduced their son to Perry’s family that day.

Best said she sees parallels between her daughter’s killing and Taylor’s case: Both women were Black, police in both cases said they fired their weapons because a man shot first and none of the officers involved in either shooting have been criminally charged.

The national scrutiny of Taylor’s killing has been a painful reminder that Kager’s death drew far less public attention or outrage.

“They’re still saying Breonna’s name, but they’ve forgotten India,” Best said. “They’re still not saying her name.”

Why fewer women are killed

The Post began tracking fatal police shootings in a database in January 2015, months after a White police officer in Ferguson, Mo., killed Michael Brown, an unarmed Black man during a confrontation. Since then, police have shot and killed about 1,000 people a year.

The starkest difference between women and men is the rate: Women account for about half the population, but 4 percent of the killings. Of those fatally shot every year, about 44 have been women.

That difference may be explained in part by broader patterns in criminal justice regarding contact with law enforcement and police stereotypes about gender, experts said. Women in the United States account for about one-fourth of all arrests, according to FBI data.

“Even when they have a confrontation with a police officer, they’re less likely to have a weapon, they’re less likely to have the same threat level as a man,” said Geoffrey P. Alpert, a criminology professor at the University of South Carolina and co-author of “Evaluating Police Uses of Force.”

Arrest data indicates how often a gender or ethnic group is confronted by police, Alpert said, but it also distorts how officers perceive the threat a person from that group poses — regardless of whether they are committing a crime at the time. Gender- or race-based stereotypes can create a false perception of how dangerous a person is likely to be, Alpert said.

“I think it’s an illusion that you look at a woman and you think of her as not being as threatening as a male. … In the aggregate that may be true, but this particular woman you may be looking at may be Bonnie,” he said, referring to Bonnie Parker, part of a criminal couple believed to have killed at least 13 people during the Great Depression.

Lawrence Sherman, director of the University of Cambridge’s Police Executive Program and the Cambridge Center for Evidence-Based Policing, agreed that police may feel less threatened by women. Police generally view men as more likely to commit homicides and carry guns, he said.

Officers also may feel more comfortable taking steps to de-escalate a situation when challenged by a woman, Sherman said. “The police officers may be seeing a challenge from a woman as less risky to their reputation” among their colleagues, Sherman said.

The chance of police using force on a woman rapidly increases if the officer perceives she is not conforming to stereotypes of women as submissive and deferential — especially if the woman is Black or LGBTQ, said Andrea Ritchie, researcher-in-residence at the Barnard Center for Research on Women.

She said the officer may view a woman who behaves that way as “hysterical” and, in turn, overreact.

“There’s definitely a long history of framing women who aren’t compliant as insane,” said Ritchie, author of “Invisible No More: Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color.”

“I think that’s particularly true for Black women.”

Some patterns in fatal shootings by police hold true for both genders.

For women and men, about one-third of the police encounters that led to shootings began with a report of a domestic disturbance, a 911 call or a traffic stop, records show.

The average age of women and men killed by police was 37, and about one-third were 25 to 34.

As with fatal police shootings of men, the vast majority of the women killed were armed with a potential weapon at the time, although slightly less often: 89 percent of the women were armed, compared to 91 percent of the men.

For both genders, a gun was the most common weapon. Of men killed, 57 percent were armed with a gun and of women, 44 percent. In other cases, women were armed with knives, cars, toy weapons, hammers and hatchets.

By race, 147 of the women killed were White, 48 Black and 29 Hispanic. Five were Native American, four were Asian and three were other races. In 11 cases, race could not be determined. By percentages, men shot by police were less often White and more often Black or Hispanic.

Since 2015, police have killed 26 unarmed women, including Taylor. Of those, 14 were White, seven were Black, four were Hispanic and one’s race was unknown. While about twice as many White women were shot and killed as Black women, White women account for five times the Black female population.

One explanation for the disproportionate numbers could be what sociologists call the “ecological fallacy,” which means people — in this case, police — act with generalizations in mind, even though they don’t know whether it applies to the person they’re dealing with, Alpert said.

“We create these stereotypes for groups, but we have no idea if that one person fits the mold,” he said.

Crenshaw offered another reason for the disparity: centuries of people associating dark skin with being a threat.

“You don’t need to have Black people being more frequently arrested to have an implicit association with Blackness and danger,” she said. “That is a deep part of our culture.”

Killed at a home

Of the 89 women killed at residences where they lived or often stayed, 12 encounters began as did Taylor’s — with a warrant to conduct a search or make an arrest in an investigation.

In two killings, police said they shot the woman by accident. In most of those cases, the women were armed or reaching for a weapon, police said.

On Jan. 17, 2018, police in Bartlesville, Okla., killed 72-year-old Geraldine Townsend when they went to search her son’s home for marijuana.

Townsend, who was Black, was sleeping inside her son’s home, where she lived, when officers conducted a “knock and announce” warrant and burst through the door, according to police records.

Body-camera footage captured the encounter: Officers ordered Townsend’s son, Michael Livingston, to get on the ground and then yelled for someone else, who cannot be seen, to put down a gun.

“I entered the hallway, stepping over Livingston and started to hear loud ‘popping’ sounds, I felt something hit my right leg and a sharp burning sensation in my thigh area,” an officer later wrote in a report.

He said he saw a woman on her knees behind a door frame 3 to 5 feet away, holding a gun. He ordered her to drop it, but continued to hear popping noises, he said.

“That’s my mother!” Livingston yelled. At nearly the same moment, a shot rang out and Livingston screamed, “It’s a BB gun! You killed my mother!”

County District Attorney Kevin Buchanan determined the shooting was justified and declined to charge the officer with a crime.

Livingston was charged after officers reported finding marijuana in a Mason jar and two sandwich-style bags at the home. He pleaded no contest and received a seven-month suspended sentence.

Livingston told The Post that Townsend was asleep when police entered the home and that she owned the BB gun to protect herself from pit bulls in the neighborhood. He said his mother might still be alive if police had given him more time to let them inside.

“I just never had a chance to do it,” Livingston said.

In October 2019, Livingston filed a wrongful-death lawsuit against the city, which was dismissed on procedural grounds in June, court records show.

In an interview, Bartlesville Police Chief Tracy Roles said the officers did not know the weapon was not a firearm and had no choice but to use deadly force.

“The matter of Ms. Townsend choosing to produce a weapon and fire it at our officers really gave them, in my opinion, no choice but to return fire,” said Roles, who joined the department nine months after the shooting.

Roles said gender is irrelevant to his officers’ decisions to fire their weapons in a confrontation. “We base it on the threat that is presented to us at that time,” he said.

On Jan. 28, 2019, Houston police were executing a no-knock warrant for heroin trafficking when they shot and killed Rhogena Nicholas, 58, and her 59-year-old husband, Dennis Tuttle, a disabled Navy veteran — both White — at the Houston couple’s home.

About 4:30 p.m., roughly 12 narcotics officers and about six patrol officers, some of them in uniform, broke down the door while announcing themselves, police said.

A pit bull charged at the first officer inside, who shot and killed the dog, according to police. Tuttle came from the back of the house and shot the officer in the shoulder, causing him to collapse on the living room sofa, police said. Three other officers were also shot by Tuttle, according to Chief Art Acevedo’s statements to reporters.

Nicholas reached for the officer’s gun, according to police. Police told The Post that seven officers opened fire, striking and killing her and Tuttle.

The officers had secured the warrant asserting that there was heroin trafficking at the home, but police said they found no heroin.

In the following months, the official narrative unraveled: An internal police investigation found that an informant referenced in the search warrant said he had never bought drugs at the home.

Acevedo accused the officer who led the raid of lying to justify it.

The officer was charged with two counts of murder, while he and another officer were charged with tampering with government records for allegedly falsifying documents related to the raid, the Harris County Prosecutor’s Office said in statements. Both officers have pleaded not guilty, and the cases are ongoing.

Mike Doyle, an attorney for Nicholas’s family, said a forensic investigator hired by both families found that the officer who fired the shot fatal to Nicholas would have been unable to see her at the time and blindly fired the shot through a wall.

Doyle said the “militarized” way that officers often execute search warrants in homes — carrying rifles and breaking down doors with battering rams — makes an escalation of force likely.

“If the starting approach is extreme violence, why wouldn’t you expect bad results way too many times?” Doyle said.

Nicholas’s brother, John Nicholas, told The Post he wants police to release body-camera video from the patrol officers and other officers who responded after the exchange of gunfire. Acevedo has told reporters that the narcotics officers who led the raid were not wearing body cameras.

“To this day, the chief of police hasn’t apologized,” John Nicholas said. “They still say there was a reason to be there, but nobody knows that reason.”

A lawyer for Tuttle’s family did not respond to a request for an interview.

Three weeks after the shooting, the Houston Police Department announced that it would severely limit its use of no-knock warrants, a controversial tool that is meant to catch suspects off-guard. Since then, the department has conducted no no-knock warrants, Acevedo told The Post.

“I immediately moved to limit no-knock warrants on the basis of the one that went horribly wrong,” Acevedo said.

Thor Eells, executive director of the National Tactical Officers Association, which provides tactical training to law enforcement, said search warrants at residences are inherently dangerous. Although police gather information before carrying out a warrant, there are unknowns.

But Eells cautioned against banning no-knock warrants. That tactic, although high-risk, is occasionally the best choice.

“It doesn’t mean it’s safe, but it’s sometimes less dangerous than other options,” Eells said.

Mental crises end in killings

In recent months, some police-reform advocates have called for local governments to “defund the police” and shift resources from police departments to public services meant to safeguard the community and its residents, including mental health programs.

About 31 percent, or 77, of the 247 women fatally shot by police since 2015 had mental health issues, compared to 22 percent of the 5,362 men killed.

In several cases, women called 911 to falsely report a crime and engaged officers with a weapon when they arrived. Other times, family members called police to the women’s homes, saying they were acting dangerously, according to The Post’s database.

The number of women and men killed in these circumstances may be explained because police overall spend up to one-fifth of their time responding to people with a mental illness, according to a 2015 study from the Treatment Advocacy Center, a Virginia-based nonprofit group for people with severe mental illness.

By the time police use fatal force against someone in mental distress, that person often has not had professional help and may be a danger to themselves or others, said John Snook, the center’s executive director.

This kind of encounter is a greater risk for a woman than for a man, Snook said, because officers may be slower to identify a woman in mental crisis and take her to a hospital. Without treatment, future interactions with police could end in a fatal use of force by officers, he said.

“We have a bias against seeing women as dangerous or violent, and their illness may not present with violence in the same way a man’s would,” Snook said. “Often, their treatment is going to be delayed because they won’t meet the standards.”

The family of DeCynthia Clements, a 34-year-old Black woman who had schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, said police in Elgin, Ill., who shot and killed her should have recognized she was in the throes of a crisis and taken steps to de-escalate the situation.

On March 12, 2018, Elgin Police Officer Matthew Joniak pulled over a car driven by Clements because it was a “suspicious vehicle,” according to an Illinois State Police investigative report, which did not elaborate. Joniak spoke briefly with Clements. When Joniak returned to his patrol car, Clements drove away and then refused to stop when he tried to pull her over for running a stop sign.

A short while later, Joniak saw Clements’s SUV parked on the side of the interstate and stopped to investigate. He called other officers for help. Several officers approached Clements and directed her to get out of the car, but she refused and brandished two knives, according to the report.

For the next hour, Clements refused to leave the vehicle. She then lit two items on fire and tossed them into the back seat of the SUV, body camera video shows, and the car erupted in flames.

Officers pleaded with Clements to get out of the vehicle. Lt. Christian Jensen told investigators that when Clements stepped out, she pointed the knives at the officers, made what he described as a “war cry” and “charged at the officers,” the report says.

Jensen told investigators that the officers, who were six to eight feet away, could not escape because they were standing against a highway barrier with patrol cars on two sides of them. The body camera video shows at least four officers near Clements’s car and more officers on the other side of the median.

Jensen fired three shots, striking and killing Clements, the report says.

Antonio Romanucci, the Clements family’s attorney, told The Post that police should have called someone trained in mental crisis intervention during the standoff. In the worst-case scenario, he said, officers still should have been able to subdue Clements with a shield when she got out of the car with knives.

The family sued the city of Elgin, alleging that officers had encountered Clements several times while patrolling the housing project where she grew up, were familiar with her mental illnesses and should have recognized she was experiencing a crisis. During the encounter, a police dispatcher told Jensen that the department had previous contact with Clements and referred to her as a “suicidal subject,” according to the report.

A spokeswoman for the police department declined to comment on the lawsuit, which is pending. The spokeswoman also declined to comment on behalf of the officers or make them available for an interview.

Clements’s sister-in-law, Holly Clements, told The Post that her family struggles with the loss of Clements, but appreciates the national discussion about how to limit the use of fatal force.

“It’s not going to ever bring back my sister-in-law,” she said. “But at least they’re trying to fix what was wrong.”

Roles, the Bartlesville police chief, said police should not be the primary responders to people experiencing a mental crisis. Organizations that provide mental health services should “take a more hands-on approach,” he said.

“One of the biggest problems that I see is that we in law enforcement, we tend to be the catchall of society’s problems,” Roles said. “I don’t think that we in law enforcement are the most equipped to handle those with mental illness.”

Like Clements, Hannah Williams had an established history of mental illness before she encountered police on the side of a California highway on July 5, 2019.

About 7 p.m., Williams, 17, was driving her family’s rental SUV east when a Fullerton, Calif., K-9 officer saw her speeding above 100 mph and drifting across lanes, according to an investigatory report from the Orange County district attorney’s office. Williams’s SUV “made an abrupt right turn from the carpool lane and collided with the front end” of the officer’s car, and he signaled for her to pull over, the report says.

The SUV skidded to a stop, and the officer walked around the back to the driver’s side. Body camera video shows that Williams, whose father said she was multiracial, was standing outside of the car facing him with her arms outstretched, holding what police said looked like a semiautomatic firearm.

The officer fired his weapon, knocking Williams to the ground. As she lay in the middle of State Route 91, the officer yelled at her to show her hands, the video shows.

Williams repeatedly cried out for help as the officer cuffed her hands behind her back. “I can’t breathe,” she said. She told the officer that she had been struck in the chest.

A retired officer, who had stopped to help, picked up the object that Williams was holding when she was shot, the video shows. It was a replica pistol — not a real weapon — he told the K-9 officer, who administered first aid. She died that evening at a hospital.

Meanwhile, her father, Ben Williams, said when he noticed she was gone from home, he searched the neighborhood and called her repeatedly.

He said that around 8:30 p.m., he called police to report that his daughter took the car without permission and that he was afraid she would hurt herself. She had been taking medication for depression, he frantically told a police dispatcher, according to audio of the conversation.

By that time, his daughter was already dead.

Fullerton police officials declined to comment, citing a legal claim for damages by the Williams family. The Orange County district attorney’s office concluded in June that the shooting was legally justified.

Hannah Williams had long struggled with severe mental illness, her father said, but she seemed to be doing better shortly before she was killed.

“She was still growing — so young,” Ben Williams said in an interview. “She still had so much to go.”

Julie Tate, Drea Cornejo, Alice Crites, Eddy Palanzo, Ted Mellnik and Steven Rich contributed to this report. Graphics by Daniela Santamarina. Design and development by Madison Dong. Story editing by David Fallis. Graphics editing by Danielle Rindler. Photo editing by Nick Kirkpatrick. Copy editing by Melissa Ngo.

Shootings data are from the Washington Post’s police shootings database, which contains records of every fatal shooting in the United States by an on-duty officer since Jan. 1, 2015.

Population data are five-year estimates from the 2018 American Community Survey by the U.S. Census Bureau. Victims whose race is not specified are not included in the graphic displaying rates by race.

The Post identifies victims by the gender they identify with if reports indicate that it differs from their biological sex. Read our full methodology and download the data.