After working for months on the PBS FRONTLINE documentary “Trump’s Trade War,” I could probably recite portions of Donald Trump’s May 1, 2016, campaign speech in Fort Wayne, Indiana, from memory. In the speech, Trump said: “We can’t allow China to continue raping our country, and that’s what they’re doing.”

The speech features prominently in a scene from the documentary that aired in May and sets up Trump’s use of China’s trade practices as a punching bag while on the campaign trail, foreshadowing the current trade tensions.

Editors Adam Lingo and Fritz Kramer constructed that scene from seven different videos of the same speech, shot from various angles both by professionals and random cell phone-holders. My colleague, co-producer Emma Schwartz, and I spent hours searching YouTube for every version of the roughly hour-long speech we could find for our editors to choose from. I think we both still had “Start Me Up” by the Rolling Stones, the opening music to which Trump walked into the event, stuck in our head for days afterward (this was around the time the band asked Trump to stop using its music at events).

“Trump’s Trade War,” which has had more than 600,000 views on YouTube, was one of the most archival research heavy FRONTLINE documentaries that writer-director Rick Young’s D.C.-based production team has created so far. It required delving deep into the history of the relationship between the U.S. and China. As the film’s title suggests, it also involved doing a lot of research on Donald J. Trump.

Spending some seven months watching footage of Trump, reading his tweets and trying to get inside his head was grueling at times. While my research was far from solely focused on the president, I probably watched far more footage of him than I did of anyone else in the film. The extensive archival research my colleagues and I did enabled us to create a more nuanced film, enriched by the diverse footage we used from sources ranging from Chinese state-funded CCTV News to Ivanka Trump’s personal Instagram account, which included cellphone video of Ivanka’s children greeting Chinese President Xi Jinping and his wife in Mandarin at Mar-a-Lago. Using that video gave a “behind-the-scenes” perspective that stock footage alone would lack.

Archival research was one of my most time-consuming responsibilities as the IRW-FRONTLINE Fellow in 2018-2019, as I scoured the internet and the archives at the Library of Congress for the best footage and photographs related to our story. The master spreadsheet of archival materials contained nearly 1,000 rows, which didn’t include late additions made during our final weeks of editing.

With the aid of Factba.se, an online database that tracks Trump’s language through his public statements and Twitter, I compiled a list of every time the president tweeted using the word “China” — nearly 190 times between May 2016 and March 2019. Although we did not end up using many of his tweets in the film, the list served as a reference timeline so we could see what Trump was saying about China at any given time leading up to and during his presidency.

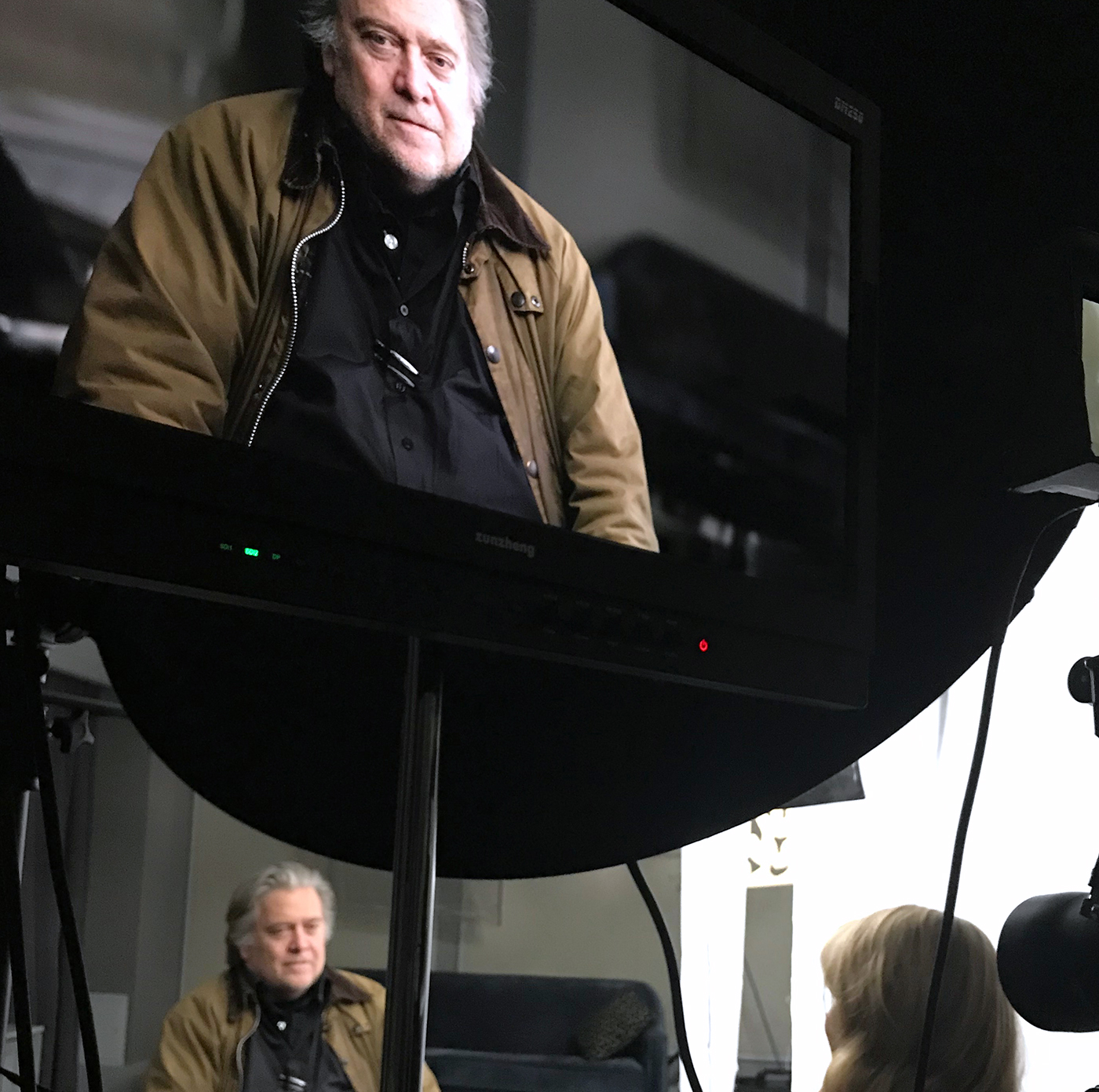

One of my favorite projects was pairing the words of TV host and commentator Lou Dobbs with those of Trump on the 2016 campaign trail. In our team’s interview with Steve Bannon, the former White House chief strategist mentioned that Trump borrowed much of his China rhetoric directly from Dobbs’ TV appearances. Shortly after the Bannon interview, I worked on finding matching phrases from Trump’s campaign announcement speech with statements that Dobbs had made on CNN and Fox News, matching their language as closely as possible. Only one of Dobbs’ lines made it into the final film, but I believe the impact of that few seconds was worth the days of research.

The archive of footage, tweets and other material our team compiled became a vast resource, useful for filling in the gaps in the story we couldn’t tell with our original footage. Because of that research, Trump and his words became essential elements in the film even though we did not interview him.